How did we make it this far?

Hi everyone. I’ve been posting mostly on Medium and Substack. Thank you for coming here. I hope you enjoy this.

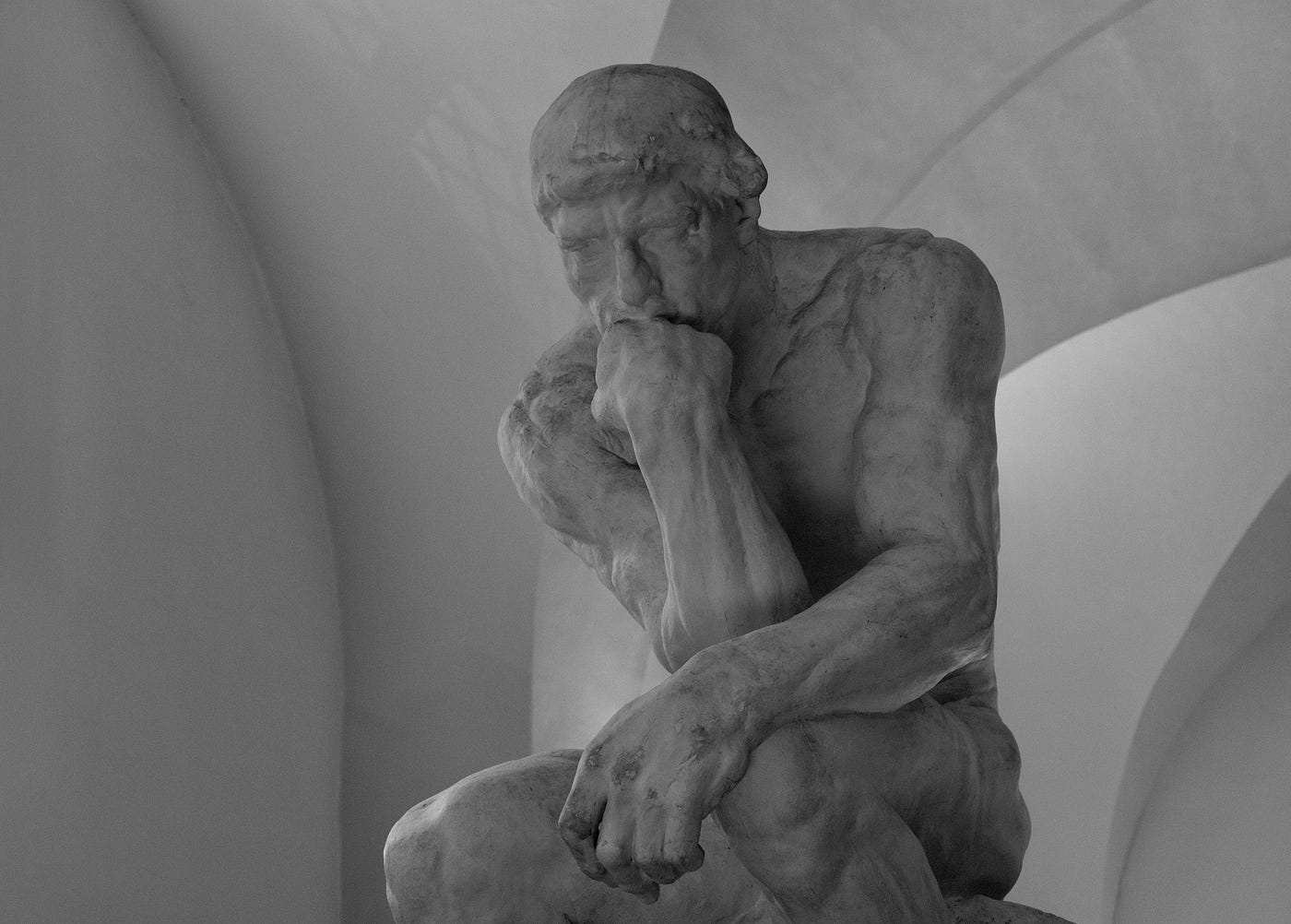

“And what is good, Phaedrus,

And what is not good —

Need we ask anyone to tell us these things?”Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (ZATAOMM), first published in 1974 and since sold over 5 million copies, is one of the most popular philosophy books. One of the central themes is the concept of quality, and the above quote captures the author’s central tenet. Quality is a feature that can’t be explained indirectly. One just knows. Pirsig was a proponent of experience informing one’s capacity to know, in addition to science.

This spearheaded a debate among scientists and philosophers about whether or not knowledge can come from within or if it depends on extrinsic validation.

The quote has great meaning to me personally. Though I embraced reductionistic science during my early career, I eventually realized the importance of non-quantitative knowing. This journey led me back to Pirsig.

At the very least, we need multiple methods of knowing, but I fear reductivism has closed the door on everything else. We must reopen it.

And so I ask the following, with due respect to Pirsig:

“And what we know, Phaedrus,

And what we do not know—

Need we ask anyone to tell us these things?”Context and Assumptions

As Pirsig suggested in ZATAOMM, experience is necessary for knowing. One can’t just ‘pull knowledge out of thin air’ (more on that later). The knowing must be informed somehow. Modernity has embraced science as the best, if not only, way we can know. My central argument here is that science is not the only way one can know, and it is dangerous to ignore alternatives.

Many speak of intuition or trusting one’s gut, and I suppose that applies to my suggestion. I am particularly curious, lately, about what happened to my gut and why it became so difficult to find it, much less trust it, as I aged. We are more connected with our intuition — their heart and gut — in our youth. However, as we age, the domestication process gradually erodes our capacity. Often, we replace our intuition with reductionist approaches, such as science.

Evidence: Indigenous Ancestors

The scientific revolution occurred about 500 years ago. Before that, we had the philosophical approach of ancient Greece, perhaps 2,000 years prior. If we believe that Homo sapiens emerged, say, 250,000 years ago, that period of recent history represents about one percent of our history.

One.

Percent.

Can we not conclude that humans were successful at persisting on Earth for 99% of our history in the absence of science? Can we agree with the assumption that we still had ways of knowing or understanding our environments and ourselves well enough to survive?

I’ll concede that the quality and quantity of life were very different. Arguably worse, but in many ways arguably better. Sure, we may not have lived as long, but isn’t it possible our lives were filled with harmony, laughter, and bellies full of meat? We’ll never know, but I am not informed enough, nor do I accept the body of evidence as being meaningful enough to close the door on that possibility. Those among us who insist Modernity is ‘better’ should likely refer to the original quote by Pirsig. And maybe even (re)read his 1974 masterpiece.

Hopefully, we can agree that it is possible that human life was better, at least in some ways, before Modernity. While it is beyond the scope of my intention here, I wonder if we might not also agree that science, while solving many of life’s problems and arguably improving things in some areas, has also created new problems that would not have existed without it. I’m looking at you, atomic bomb.

Ancestral Learnings

How did our ancestors know things without the Earth-shattering tools of science? Pirisg would say, ‘experience’, philosophers, reason. But what are these, exactly?

At the very least, humans are inhibited by and endowed with six basic senses. These are sight, hearing, touch, smell, and taste. The sixth sense is the mind or nervous system that facilitates the interpretation of these senses into meaningful information we use to influence our behavior.

What can we possibly determine about ourselves and our environment using our six senses? While I do not know the extent of our capacity to know, what I can say is that we cannot know everything. By extension, we also cannot know if our determinations or conclusions are accurate. In the end, what we know is a version of reality. An explanation of the truth. A story we tell ourselves to solve a problem, meet a need, or get through the day.

Knowing, then, is separate from truth. Briefly, I separate the world of knowledge and reality into realms. There is the known, the stories of the world we tell ourselves, the unknown, or the parts of the world for which we have no story, or are unaware of, and the unknowable.

Necessity: The Mother of Invention

Our attention is the tool with which we interact consciously with the world. When this attention is directed with purpose, it is intention. When we intend to understand the world around us and are driven by curiosity, we can learn.

As humans, we have a natural ability to bridge the gap between the known and unknown. Mindfulness maintains an open awareness and minimizes judgment. If we are open to what we observe, without trying to make it one thing or another, we can see things for what they are.

Similarly, mindfulness facilitates patient observation and delays the drawing of conclusions until evidence reaches a threshold where consensus is apparent. We don’t need to explain what we are observing immediately. Our curiosity is allocated according to the object, not our need to know.

While I don’t fully understand how to teach someone to pay attention, our ancestral relationship with our environment has surely taught us to do so. Our persistence on Earth for perhaps 300,000 years, coupled with our complex neurology, reflects a delicate and informed relationship.

Before science, before philosophy, humans understood their environment. We were not biased by objective needs or driven by selfish goals. Our survival depended on our ability to interact at time scales relevant to our needs. We learned to procure nutrients, maintain shelter, and reproduce future generations. We would not have made it otherwise. The question then is how?

Humans are (Extremely) Biased

Humans have inherent bias, and this complicates modern thinking. Science requires bias to be minimized, but this is often impossible. Scientific intent can be small and related to curiosity, but it is nearly always complicated by other human factors.

Ego, job security, and funding procurement are but a handful of biases that infiltrate modern science. No one is to blame, but the idea that any science adheres to the well-established rules is rubbish. Modern science requires us to identify and interpret findings in the context of whatever biases are present.

Efforts have been made to minimize human bias in modern science, but these fall short of achieving their goals. Three methods stand out as the gatekeepers of bias: training, statistics, and peer review.

Scientists require training, but don’t receive ethical or moral education in bias reduction. More likely, we assume that someone willing to complete a rigorous training would simply be ‘good enough’ to understand their own biases and appropriately minimize them. It is left to the individual with only two objective filters to help.

Science requires statistical analyses, but these techniques are more often used as smoke screens than true objective analyses. Science reduces the world to a set of objective numbers. This reductionism facilitates the use of mathematics to address questions of yes or no, up or down, and black or white. Statistics tell us whether to reject or fail to reject subjective hypotheses. Unfortunately, statistics can be quite complex, diverse, and when they stray outside a narrow band of tools, can confuse scientists and non-scientists alike. The process of peer review necessitates a common statistical language, and often it is this area that the scientists abuse the most.

Peer review requires that the ideas, methods, statistics, and inferences be agreed upon by other scientists. It’s as if we understand our human bias is so strong that we need others to help us see where we might be blind. Scientific peers assess the work to determine whether it adheres to the rigor required for us to trust the results.

Another form of peer review occurs but is not considered a part of the scientific method: public review. Though we are not peers, science does not become applied until it enters the zeitgeist somehow. Because there is no established mechanism to actually deliver science from the scientific world to the regular human world, this happens quite haphazardly. Usually, it is some form of media or journalism.

Often, universities or companies share their science with a general audience. These press releases skip over the important parts to deliver the findings in an easily digestible form. These are often skewed by whatever bias the organization needs to serve its main interests, often financial. So something like, “some patients who ate candy bars showed signs of improvement’ becomes, ‘M&Ms cure cancer.’ It’s hard not to do.

The Difference Between Bias and Love

Recently, I read a Substack post by Rich Blundell called “Love as a Way of Knowing”. Briefly, Blundell describes how love is a merging of the human mind with the environment in which it exists. His writing more elegantly describes what I’m getting at, which is that we have inherent ways of knowing our world, and this could be what we call Love.

Regardless of etymology, this is another example of how humans might come to understanding, comprehension, and learning without external methods, guides, or techniques. What if the ability to understand our world comes with us at birth?

And, why wouldn’t it? And why isn’t love a worthy approach to understanding? Human knowledge before the advent of science was driven by curiosity and a desire to understand. Eventually, science diluted curiosity and became about finding causal relationships.

The Problem Science Tries to Solve

Attributing, some would say proving, causality is the holy grail of understanding. Sorry, science, but you rarely do this absolutely. Science does not generate proof; it generates evidence. It is up to us, the ultimate peers, to determine whether we believe it or not. Like a dictionary, humanity is a repository for what we believe to be true. Words like truth and proof are absolutes, and we just don’t work like that.

What we call proof and truth are just dogmas. Consensus-based conclusions built around mutual faith that our belief systems align. Faith is not necessarily related to whether we find the evidence convincing. Faith itself is a form of bias, but it is combined with science to establish proof and truth. And, like it or not, consensus is based at least as much on non-science as science. Charisma and apparent authority go a much longer way than evidence most of the time.

I get a lot of hate for the above ideas, but I can’t escape the evidence. There is no mechanism in science for definitive or absolute conclusions to be drawn. The best we can do is fail to reject or support a hypothesis. Where in that do you see anything resembling proof or truth?

A single iteration of science produces a piece of evidence. One. Piece. As more and more pieces agree, we start to build precision. At some point, individuals and society writ large decide to mostly agree that the evidence does, indeed, support whatever hypothesis or inference the scientists relate to the statistics.

Because science is a human creation, it is susceptible to human flaws.

Like any other belief system, science tries to be more accurate and less, well, human in trying to form a consensus. And it probably does a better job than most other existing dogmas, like religion or familial hierarchy. But the reductionist nature of science, which tries to put a single silver-bullet causal variable in every chamber, led us to throw the baby out with the knowledge-seeking bathwater. As a result, we minimize and reject all other ways of thinking. Or we go to war over them.

Science is an important tool to have in our understanding toolbox. That we abandon, ridicule, and fight over other ways of thinking and knowing ought to tell you everything you need to know about its value in isolation from others.

Is knowing, then, the result of using every tool simultaneously?

Parsimony and Intuition

Often, the simplest solution is the best one. Science is good at obfuscation, which should also make one suspicious. The best methods of knowing are sensible and obvious to a majority of people. Not only does this work with groups of people, but it also works for most biological communities. Simple is always going to be better than complex.

That we learned enough to survive 300,000 years as a species counts for something. And, sure, the technological revolution of Modernity artificially extended our ability to survive a bit, but that’s really only the most recent 2% of our evolution. What was going on during that first 98%?

This is a much more interesting question than those pursued by modern science. But that is just my opinion. My interest lies in the fact that our early knowledge was derived not through systematic or dogmatic thinking techniques, but in our complex neurology. We made sense of the world using our senses. Our eyes, ears, hands, olfactory capacity, and taste. The Buddhists add one more, and I agree: the mind. The five senses provide the stimuli, and the mind interprets them.

Like science, humans use our minds and associated sensory receptors to draw inferences from our environments. Both systems use evidence to tell a bigger story. Is evidence derived from our biological nature less real or valid than that from experimentation? I argue they are at least comparable.

But is intuition valid? Many will say no. Many cite the idiocracy of social media as an example. Those who believe Tylenol causes autism are not good examples of intuition. While there are schools of thought that tell us to ’trust our guts’ and ‘listen to our intuition’, these methods of thinking are largely discounted as leading to mere opinion rather than meaning.

Everyone Has an Opinion

The problem is we confound intuition with opinion. Opinion does not need to be informed. One really can just choose from an array of options and say it now belongs to them. Worse, we often confound opinion with fact just as we wrongly associate fact with truth. A fact is something humans agree to be true, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be true in the universe.

For example, we used to think planetary orbits cause a gravitational pull toward the planetary core. We believed, nay, thought it to be TRUE, that a planet’s core pulled us downward like a magnet. We called this truth when it was a simple fact. Now that we have another agreed-upon explanation for gravity, the facts have changed. The truth, however, remains the same. Whatever causes gravity still causes gravity. Whether our explanation of space-time wrapping around objects is the truth, we will never know.

Opinion and intuition are similarly different. Intuition requires attention and knowledge. Intuition results from an intimacy with oneself and with one’s sensory receptors. Intuition is intentional. Intuition is practiced and honed through time. Intuition is dynamic and has an element of adaptive management that requires the individual to assess and monitor the apparent accuracy of inferences drawn.

Opinion, on the other hand, requires no rigor. We are entitled to have opinions about anything. Unfortunately, we conflate opinion with fact. We say things like, ‘Vanilla is better than chocolate’ when we mean we prefervanilla. We abused this vocabulary to the point where we no longer know the semantic differences between words like truth, fact, idea, and opinion. We confuse our own thoughts about something with the definition of that something. We believe we think, therefore it is true.

Rigor and Paying Attention

Anyone can have an opinion, but only the diligent can use intuition to understand the world. Understanding requires at least an approximation of accuracy. I imagine early hunters would not be as successful if they guessed at prey behavior rather than studying it.

I think about Einstein a lot. We consider him one of the greatest scientists to have ever lived, but did he do any actual science? What do we think about when we think of science? Mostly, it is what I describe here. Designing studies and experiments to collect samples from the world, convert the measurements to numbers, use statistics to tell us whether our hypotheses are refuted or supported, and then convert this back into our language. What data did Einstein collect?

Einstein’s experiments were in his head. He called them ’thought experiments’. I call this intuition. He came up with theories using his mind and five senses, and other people did the experimentation. He did no actual science as we traditionally think about science. What Einstein did more closely resembles intuitive reason than experimentation. Yet, we consider him to be a great scientist. Why not look at him as a great visionary? A dedicated and highly trained thinker? How about a shaman?

Ancestral Knowledge

Imagine what life would be like if we erased all prior knowledge at the onset of the scientific revolution. We assume that the vast majority of human knowledge was learned in less than 0.2% of our existence on earth. We assume we knew nothing before. Or worse, that what we knew was wrong and savage.

And we kind of did that. We assumed all ‘ancient’ knowledge was silly and wrong. We believed we were cannibalistic savages incapable of civil discourse. We painted pictures of our ancestors so flippantly disrespectful that it makes you wonder how we’d treat our enemies. Eventually, we’d see exactly how that goes and, well, it makes you wonder who the real savages are.

At the very least, I find it hard to believe humans would have made it if we had been terrible. Natural selection suggests that persistence indicates success in a given environment. Over the estimated 300,000 years we have been on the planet, the environment certainly changed. Our capacity to adjust, acclimate, and adapt is reflected in our being here now. Something went right.

Part of our evolution is about how we interact in groups. Humans are social and cooperative. Our ability to get along is most definitely causally related to our appearance on the planet in 2025. Whatever our ancestors did to get along is part of our history. A good part.

Complex Neurology

That our ancestors were able to persist for hundreds of thousands of years — countless generations of families and societies — is meaningful. If you believe in evolution and natural selection, this suggests humans made good choices. Sure, luck was involved, but at least a few things we did contributed to our success. Things like cooperation, communication, and curiosity were likely maladaptive traits we developed that we still (sometimes) practice today.

But how did we make these choices? How did we know how to think? Without science or philosophy? Without complicated languages? Without smartphones (gasp)?!

Obviously, we knew things. If you compare us with what we know about the evolutionary history of other animals, we likely developed ways of knowing over time. This is reflected in the evolution of our nervous system. Our brains got bigger, our senses more perceptive, and more energy was allocated to getting along in groups. These things improved our capacity to adapt and facilitated our persistence.

Knowing

The increased complexity with which we came to decode environmental stimuli differentiates humans from most other animals. Our minds interpret signals in ways that enhance our capacity to survive as individuals, and our ability to share our experiences with others. Together, these abilities help us survive changing environments.

Developed over thousands of years, whatever means we had of understanding our environment likely reflected things we still do today. Awareness, attention, intent, patience. Connectivity to our environment and the ability to learn. Understanding. Comprehension. None of those things requires a lab coat or government funding.

I don’t see good arguments against our ability to know things without the aid of rubrics beyond that with which we are evolutionarily armed. Everything we need is already inside us. What we are doing wrong, and what likely differentiates opinion from knowledge, is how we live our lives.

Living

Modernity has created unprecedented convenience. Rather than capitalizing on this privileged free time by being open to Nature, connecting, and living in states of curiosity, we filled the open space with distraction. Somewhere along the human evolutionary line, we became complacent. We stopped living.

I like to imagine, with generous speculative license, that we used to be filled with awe and wonder for the world around us. Like children, we could never exhaust our curiosity for the world we lived in. Whether pondering the flights of bumblebees around flowers, the curves of our neighbors’ hips, or patterns in the clouds, I think our environment was our distraction. A distraction that coincidentally taught us important things.

With modernity, technology, and convenience, we shifted from being entertained by the world around us to the world we created. The created world is helpful in many ways. Modernity and science have helped us live longer, survive more easily, and meet our basic needs with less energetic requirements. They have also created new diseases, both physical and mental, and seemingly made us more complacent and less curious. We have, in effect, disconnected from the natural world in favor of our created world.

Let’s face it. Our reality is what we perceive. Modernity has shifted our focus from the world around us, including people, to the world inside our technology. Whether stone tools or an iPhone, our creations changed nature. And many would argue that this nature is just as natural as a tree because we created it, but there are differences.

Very little about our technology enhances our experience in the world. Yes, stone tools, medicine, and air conditioning make it easier for us to meet our basic needs, but they aren’t additive to experience. If anything, technology, modernity, and science reduce our experience of the world.

A Return to Knowing

What I hope for, and what I am trying to understand, is a return to a more flexible way of knowing. The world is not absolute. Yes, there are seemingly fundamental patterns like how atoms bond or how water changes state, but most of our world is ambiguous. Trying to understand nature is like the sound of one hand clapping. Sure, you can come up with an explanation, but does it really satisfy the threshold for proof or truth? And, more importantly, does it matter?

Our need for absolute truth has obfuscated our need for tranquility. Being human should not be about mastering any part of our environment or existence. Knowing ‘enough’ to satisfy our basic needs is sufficient, and pushing that relationship beyond its capacity is folly.

“What is enough, Phaedrus? And what is not enough — need we ask anyone to tell us these things? “

Perhaps this is the real question for the modern philosophers.

May our threshold for truth accommodate our need for peace.

Discover more from Revolutionizing human evolution

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.